The Romance of Canada 4: Escape to the Barrens

Nicholas Dawidoff, “The Man Who Saw America” (NYT Magazine, July 5, 2015)

Nicholas Dawidoff, who appeared here before in the guise of a football writer, has a fascinating article about photographer (best known for The Americans) and filmmaker (best known for Cocksucker Blues) Robert Frank in the NYT Magazine. It’s worth reading on its own merits, but Canada does play a small role, when Dawidoff describes Frank’s reaction to his own growing fame:

Acclaim was likewise anathema. By the 1960s, just as his work was gaining a following, Frank abruptly moved on from still photography to become an underground filmmaker. Ten years later, with all the glories of the art world calling to him, Frank fled New York, moving to a barren hillside far in the Canadian north. (42)

“A barren hillside far in the Canadian north” — how romantic that sounds! Later in the article, however, it turns out that the place he moved to was Mabou, Nova Scotia. Here’s Dawidoff’s description of the move:

Overwhelmed in New York, craving ‘‘peace,’’ Frank asked [June] Leaf [his girlfriend] to go to Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, to find them a home. It was winter. She bought a pair of thick boots and flew north: ‘‘He knew I’d do anything for him,’’ she says now.

They moved to Mabou, where the March wind was so strong you had to walk backward. They knew nobody, and the house they’d purchased overlooking the sea was, in the local expression, ‘‘after falling down.’’

Now, if you consult a map, you will see that while Mabou may be barren, it is roughly as far north as Maine. (If Frank is “the man who saw America,” Dawidoff is “the man who never saw (a map of) Canada.”) It’s a bit troubling that this kind of error can make its way into The New York Times (even if only the magazine) — doesn’t anyone check these things? Do the editors really think a place that’s much closer to Martha’s Vineyard than to the Arctic Circle represents the “far north”? Perhaps they think anywhere in Canada is the far north. Or perhaps this is just another instance of Americans’ total indifference to our country and everything to do with it.

Beyond that, Frank’s girlfriend saying that flying to Nova Scotia proves that she would “do anything for him” is quite charming, suggesting, as it does, that travelling to Nova Scotia is a perilous undertaking from which one is fortunate to return alive. And while Dawidoff doesn’t say it directly he certainly implies, through the references to the thick boots and the strong March wind, that Canada is cold — one of the most common ideas about our country.

The main impression of Canada conveyed by this article, however, is that it is a remote, unpopulated land that is ideal if you’re looking for somewhere to escape to. (We saw a similar attitude to Canada in Kris Kraus’s novel torpor.) And perhaps I’m imagining things, but I even feel like there is a certain admiration in Dawidoff’s tone as he describes Frank’s abrupt departure from New York. We do tend to idolize great artists, and far be it from me to suggest that Frank doesn’t deserve Dawidoff’s adulation; but there is a special reverence reserved for those who not only produce great works of art, but who also reject the trappings of fame and celebrity that come with their accomplishment. The reclusive genius is a romantic figure, admired for being more honest and true to the artist’s calling by virtue of having rejected fame, and in describing Frank’s flight to Canada, Dawidoff places him firmly in that category.

And so Canada plays a role here, not as an independent nation with an identity of its own, but rather as a marker of authenticity that validates a particular kind of American achievement: ironically, it is by leaving New York for Canada that Frank establishes his status as a true American original, a genuine artist not interested in his own fame but devoted only to the tough realities of his art.

What, after, all, could represent a more complete rejection of fame than leaving New York City (and “all the glories of the art world” — what are those, I wonder?) for Canada? And not just Canada, but a “barren hillside” in the (supposedly) “far north”?

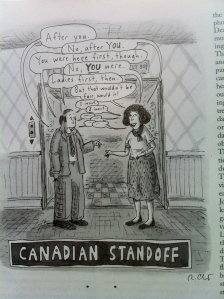

In fact, there are probably areas in the United States that are just as much a wilderness as the most wilderness-y areas of Canada; and yet escaping to a cabin in Montana doesn’t have the same romantic finality, the same grandeur in terms of a gesture, as fleeing to Canada, where of course acclaim can never pursue you because, as everyone knows, in Canada the mechanics by which acclaim comes to be don’t exist: there are no magazines, no newspapers, no television, no radio, no people or communities; just an endless succession of barren hillsides where American artists fleeing their own celebrity huddle together to stay warm against the unending cold.