Who Can Tell Canada from the Cayman Islands?

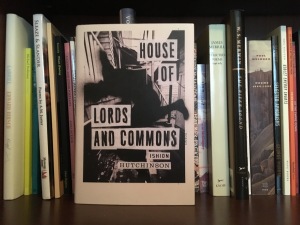

Ishion Hutchinson, House of Lords and Commons (2016)

The poem that mentions Canada is called “Pierre” and is a sort of character portrait set in a school, presumably in Jamaica. It’s a bit long, but I hate chopping up poems unnecessarily so I’ll quote it in its entirety:

It was a boy named Pierre Powell

who was in charge of the atlasin the cabinet. He also ended days

by shaking the iron bell from PrincipalWilliam’s window, a work we grudged

him for very little; what cut our corestwice a week and we had to endure,

was him being summoned to fetchthe key, again from William’s office,

to open the varnished box with the worldmap, old and laminated, a forbidden

missionary gift trophied beside the OxfordSet of Mathematical Instruments and other

things seen only by Pierre and teacher Rose,who now only nodded to raise him

to his duty. We waited in quiethis return, Miss Rose all crinkled blouse

and bones with chalk dust in her hair,did not stir until he was back, panting

at the door. Another diviner’s nodand he opened it, unrolled the map expertly,

kneaded out creases and held down edgesfor the ruler our eyes followed,

screeching out countries, and etchedin the periphery, a khaki-pillared Pierre,

with a merchant’s smile, a fixed blurin our cry of Algeria, Switzerland, Chile,

soon withered away, and we eyed the fieldof dry grass outside, a rusty mule,

statue-frozen in the punishable heat,Pierre, a phantom sea fraying

over Antarctica, Fiji, Belize, Indiaof those still in the rote, a liturgy of dunce

bats, whose one cardinal point, TropicanaSugar Estate, so close we could smell the sugar

being processed, whistled its shift change,and terminated Geography. As if punched

from dream, those of us spared the map-rolling-up and cabinet-locking ceremony,

saw him, with a cord-strung key, an earnest airbearing him away in a portal of sunlight.

He was absent the week before summer,and when Miss Rose, in rare fashion,

inquired, a girl said he had gone back home.“Home,” Miss Rose sounded the strange word.

“Home,” the girl echoed and added, “him from Cayman,Miss, or Canada, somewhere with a C.”

We turned to Miss Rose to clarify Canadaor Cayman, this elsewhere C curdled

to snow in our minds; foreign always spectral,but she pointed anonymously a crooked

finger and said, “Run to the principalfor the key,” the whole class scattered, paid

no heed that not a single one was ordained. (36-39)

Beneath the “school days recollected” subject matter lies an intriguing subtext about the after-effects of colonialism. The map, which is called a “missionary gift,” and the set of Oxford Mathematical Tools are relics representing Jamaica’s time as a British colony. Within the school a system of status and power has been created based on proximity to these objects, which echoes the colonial system itself. This hierarchy separates those who are allowed contact with the objects stored in the locked cabinet — the principal, the teacher and Pierre — and the rest of the students, who can only look on as these objects are paraded before them. The poem focuses on the resentment the other students feel at Pierre, the one chosen to handle these precious “trophies”. When Pierre disappears, the teacher is for some reason unable to deputize another single student to take over his duties, and the “teacher’s pet” system (like colonialism?) collapses into scattering chaos.

With the mention of Canada, a note of humour enters the poem. The joke, of course, is that after all the time with the map and the shouting out of countries in geography class, the student is still confused about “Canada” versus “Cayman” — the latter presumably meaning the Cayman Islands. This is a strikingly odd confusion, since the letter “C” is about the only thing Canada and the Cayman Islands have in common. Just the climate alone — as I write this, it is -5 C in Toronto, feeling like -12 and snowing heavily; in George Town, in the Cayman Islands, it’s 28 and sunny.

The question of where Pierre is actually from is never directly answered, as the teacher, when the students turn to her, offers no clarification. We do have these suggestive words:

…this elsewhere C curdled

to snow in our minds; foreign always spectral…

This couplet gives us as much resolution as we’re going to get on the question of Pierre’s homeland. I’m not sure I can parse the exact prose sense of the “C curdled to snow” — perhaps the idea is that snow can be lumpy, like milk when it curdles? — but the mention of snow does seem to suggest that Pierre is actually from Canada and not the Cayman Islands. Why else would snow suddenly enter the poem?

But then the following words, “foreign always spectral,” undermine the inference by suggesting that, to the children in the class, anything outside their homeland remains vague and mysterious to them despite their teacher’s efforts to drill them in geography. Maybe the snow in the poem carries different associations: perhaps it symbolizes something ephemeral — snow melts, after all. And so for the children in the class, the question of where Pierre has gone, the question of Canada or the Cayman Islands, creates only a vague and passing sense of some other, foreign place in their minds — an association that then fades like melting snow.

However one takes “Pierre,” we have Canada and snow brought together, which indicates that at some level, even if only subconsciously, the idea that Canada is cold and snowy has percolated into the poem. And this, of course, is one of the most common ideas about our country.