So Polite It’s … Creepy

P.C. Vey, “Whack A Canadian,” from The New Yorker (February 23 & March 2, 2015)

I have to admit there are moments when even I grow tired of thinking about Canada. And I suspect that most people have even less tolerance for Canada-related thinking than I do. In fact, people in general probably find thinking about Canada rather wearying, even at the best of times.

There is one group of people, however, who have demonstrated time and again that, when it comes to thinking about Canada, they are indefatiguable. Who are these people, you ask?

Why, New Yorker cartoonists, of course.

For them, it seems, jokes about Canadians are an inexhaustible well of hilarity, one whose brackish waters they go back to draw from again and again. Above is a recent example; if you can’t read the caption at that size, it says, “I just want to apologize beforehand if you miss.”

I have already laid out my Platonic theory of New Yorker cartoons, and I’m not going to go through it again here; you can click on that link and consult it if you like. The cartoon above represents yet another iteration of what is perhaps the most common type of Canadian New Yorker cartoon: “Canadians are so polite that….” So polite, in this case, that we would apologize in advance to someone who might fail to whack us on the head with a mallet.

The precise joke in this particular cartoon is a little elusive, at least for me; at first I thought it meant, “I want to apologize in case you miss because I’m so polite that I will feel bad for you if you fail to hit me and therefore don’t win a prize.” After further reflection, though, I think the joke is actually based on the idea that Canadians are so polite that if you step on a Canadian’s foot, the Canadian will apologize. Read in that way, the joke means something more along the lines of, “As a polite Canadian, I plan to apologize if you hit me on the head with that mallet, but I’m actually so excessively polite that I want to apologize in advance just in case you miss me and leave me with no reason to apologize later” – as if apologizing for suffering physical violence were such a thrill for Canadians that we don’t want to lose any opportunity to do so.

Either way, the cartoon suggests that Canadians are so polite that it is weird, and perhaps beginning to border on the creepy.

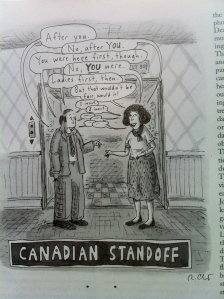

There are even visual similarities between this cartoon and previous Canada-related cartoons in The New Yorker. For comparison, here are a couple we’ve looked at before. The “Canadian Standoff” cartoon:

And the “Canadian Lemmings” cartoon:

In all three, the word “Canadian” appears prominently, paired with something already familiar to readers: a standoff, lemmings, and replacing the word “mole” in the game Whack-A-Mole. All three cartoons are also by different artists, which suggests either that these ideas about Canada are so common that all Americans share them, or that these cartoons are being generated according to some proprietary New Yorker “polite Canadian” cartoon template.

But there’s really nothing new in any of that.

What is new is the strange undercurrent of violence in the “Whack A Canadian” cartoon, which is essentially about an American (presumably) who is going to attempt to clobber a Canadian with a mallet as part of a carnival game. In other Canada-related New Yorker cartoons, Canadians have been portrayed as if they were slightly weird relatives: a little different from Americans, but harmless, really, and maybe even a bit lovable on account of our odd foibles. What accounts for the edge of viciousness in this cartoon? Are our southern neighbours beginning to turn against us? Are we so polite that we have transformed politeness into a form of passive aggression that needs to be combated with direct violence?

Or perhaps there’s another issue here – is the cartoonist frustrated at not being able to come up with anything but another “polite Canadians” cartoon, and so he is subliminally taking out his anger against us, as if it were Canada’s fault that his inspiration had flagged? Or perhaps the Canadian cartoon was imposed on him by New Yorker Cartoons Editor Robert Mankoff, who seems to have a fondness for this sort of Canadian joke, and the violent attitude against the Canadian in the cartoon is just the expression of the cartoonist’s attitude towards his material?

Or is it just a cartoon, and I’m a hyper-sensitive Canadian reading way too much into it?